Issue #3: Rich Worker or Poor Capitalist? Understanding Class Beyond Income

"You think you're so clever and classless and free, but you're still fucking peasants as far as I can see. A working class hero is something to be" – John Lennon

This issue is based on Chapter 4 of La Frustración de Prometeo by R.Gallego , expanded to add additional examples and clarifications.

Society Divided: Workers and Capitalists

For the purpose of this discussion, we divide society into two principal classes: workers and capitalists.

Workers live primarily from the income generated by their labour, whether physical, intellectual, or emotional.

Capitalists live primarily from capital income, money earned through ownership of assets like businesses, real estate, or stocks.

Labour income might seem straightforward; it’s what you get for working. But in a capitalist society, not all wages reflect labour alone. Some so-called “salaries” include built-in capital income disguised as pay.

Labour income is the compensation someone receives for contributing their skills and time to producing a good or service, but for it to qualify as labour income, it should reflect the market value of the work itself, not be inflated by ownership, status, or insider access.

A high school teacher earning €35,000 a year is a worker. Their income is tied directly to their labour.

Now, take a CEO who “earns” €5 million a year. That person may “work,” but their income far exceeds what the market would pay for comparable labour. Much of that income comes from their position of control, via stock options, insider access, or boardroom influence, not from labour. Though legally a salary, it functions as capital income in disguise.

Clarifying Capitalists and Rentiers

Capitalists aren’t necessarily people who don’t work. Some work long hours. What defines them is not effort, but where most of their income comes from. The ones who don’t work at all are called rentiers.

A hedge fund manager might technically have a job, but if their income is mostly from fees, dividends, and capital gains, they are a capitalist, even if they show up every day.

If the economy were ever socialised, business owners would lose their capital income—the profit from ownership—but not their labour income. If they continued working, they’d earn based on their skills and contribution, just like anyone else.

That’s not discrimination. It’s equality of labour.

Can a Capitalist Be Poor, and a Business Owner Be a Worker?

Yes. Class isn’t about how much money someone has, it’s about how that money is earned.

A person living off €5,000 in dividends with no job is still a capitalist. They live off ownership, not labour. That’s rare, but clarifying: class is structural, not personal.

On the flip side, someone can own a small business and still be a worker.

If they work full-time, earn a modest income, and their self-paid salary is similar to what the labour market would offer for the same work, then, even as owners, and especially if they can’t stop working without losing it, they belong to the working class.

This includes gig workers, influencers, streamers, freelancers, and content creators. They may be labelled as “entrepreneurs” but if they have to constantly hustle, delivering food, posting content, streaming, to survive, then their income is tied to labour, not ownership.

But if the business starts producing profit without their labour, they cross into capitalist territory.

That transition isn’t about effort, it’s about extracting surplus value from others.

How Definitions Shape Ideology

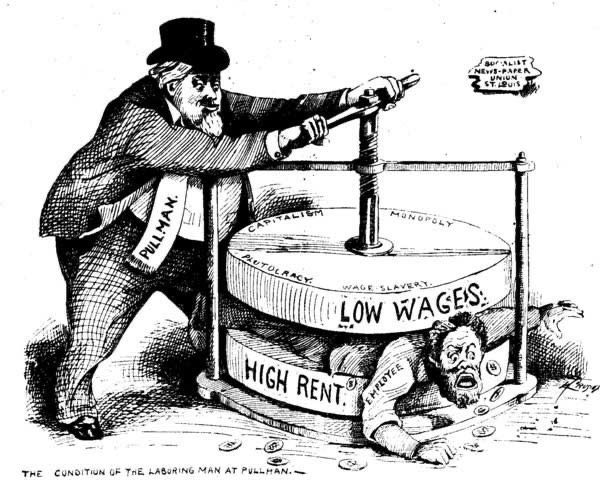

In the early 20th century, revolutionary movements insisted on one truth: capitalism rests on exploitation. Class struggle wasn’t just a slogan, it explained history. Workers produced value. Capitalists extracted it. That tension shaped everything from wages to wars.

But as socialist uprisings were crushed and liberal democracies stabilized, the language of class got muddied. Politicians, media, and institutions replaced “workers” and “bosses” with softer terms like “middle class,” “consumers,” or “taxpayers.”

This shift protected the status quo.

Economic roles were reframed as cultural identities. A delivery driver and a landlord could both be called “middle class.” A striking nurse and a hedge fund manager—“taxpayers.”

Class became about lifestyle, not labour.

If people stop seeing themselves as workers, they stop organizing like workers. This ideological confusion stretches back to Marx: ideology reflects the interests of the ruling class. Today, in Spain, the U.S., and across Europe, we hear about “working families” and “the middle class” but rarely about capitalists or class conflict. Why? Because naming class means naming exploitation, and who profits from it.

Aspiration Replaces Class Consciousness

This confusion shapes how people see themselves.

Workers are told they’re already capitalists because they own pension shares or rent a spare room. But if your job brings in €2,000 a month and your rent income brings in €500, you’re not a capitalist. You’re a worker with savings.

Still, even small ownership can shift your political alignment. A teacher with a rental flat may oppose rent control. A bus driver with mutual funds might oppose strikes that threaten market stability. This is how capitalism reproduces itself, not just through institutions, but through aspiration.

The wealthy are praised for “working hard”, but what they have is proximity to capital, market dominance, and political leverage. Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg don’t just run companies, they influence tax laws and labour policy to protect their profits and suppress competition. Amancio Ortega (Zara, Bershka, etc.) benefits from real estate deals, public subsidies, and outsourced labour

They aren’t rewarded for working harder. They’re rewarded for controlling the system.

What Class Really Means

Class is material. It determines your objective interests, what materially improves your conditions, whether or not you realize it.

Workers’ interests include:

Higher wages

Expanded public services

Free education and healthcare

Housing as a right

Full employment

Capitalists’ interests include:

Lower wages

Cuts to social spending

Privatized education and healthcare

Housing as a commodity

Structural unemployment leads to lower wages and reduces workers’ bargaining power.

Sometimes those interests overlap, but rarely. Protecting the environment may help everyone, but even then, that means challenging the private interests that profit from pollution, waste, land grabs, or deforestation. In these cases, capital tends to resist reform, even when it’s in the public interest.

Workers are often kept from seeing their interests clearly. Capitalists are clear on theirs.

From marketing to media, the system encourages class confusion. Not by openly denying class, but by replacing it with stories of personal success, celebrity aspiration, or lifestyle branding. If you’re told you can “make it” by working hard enough, why organize for systemic change? We’ll explore those narratives in a future issue on ideology.

But for now, what matters is this: your material position, not your identity, opinion, or income bracket, determines your class interests.

Surplus Value: Why Conflict Is Built-In

The clash between labour and capital isn’t about whether individual capitalists are good or bad people. It’s not just about greed or selfishness. It’s about how the system is built, structurally, to extract value from labour.

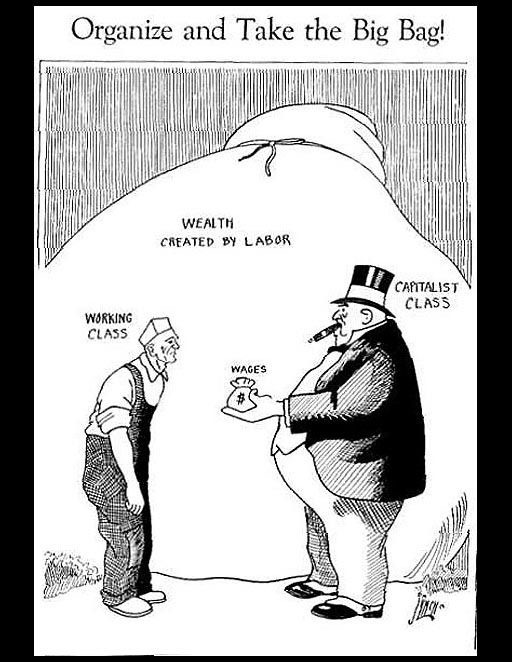

Capital income doesn’t come from work. It comes from owning the right to claim the value produced by others.

In every production process, whether in a factory, an office, or an app-based gig, only human labour creates new value. Machines and materials don’t generate profit; they just pass on their cost. It’s human labour that produces more than it consumes.

That extra is called surplus value.

A garment worker earns €2 to sew a shirt. Materials cost €5. The shirt sells for €40. The remaining €33 is surplus, divided between brands, factory owners, retailers, and shareholders.

That surplus becomes profit. And that profit becomes capital, or as Marx put it, “dead labour”: the stored-up value of work done by others, now owned by someone else.

The lower the wages, the higher the surplus.

That’s why capitalists push to cut wages, through outsourcing, automation, or union-busting, while workers fight to raise wages and improve conditions.

This represents materially opposed interests.

It’s why no amount of reform can make capitalism fair, because its basic logic depends on paying workers less than the value they produce, and extracting more than it gives.

Why Class Clarity Matters

Understanding class is essential.

It shapes how we vote, how we organize, and who we fight for.

When we understand who works, who owns, and who profits, we stop blaming the wrong people: immigrants, trans people, single mothers, the houseless, the unemployed, striking teachers, or students in debt.

Class consciousness isn’t about feeling guilt, it means realizing:

“I am a worker. My interests are tied to other workers. And I should act in alignment with those interests, economically, politically, and socially.”

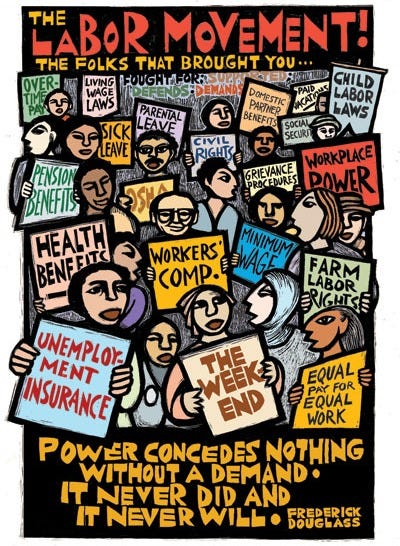

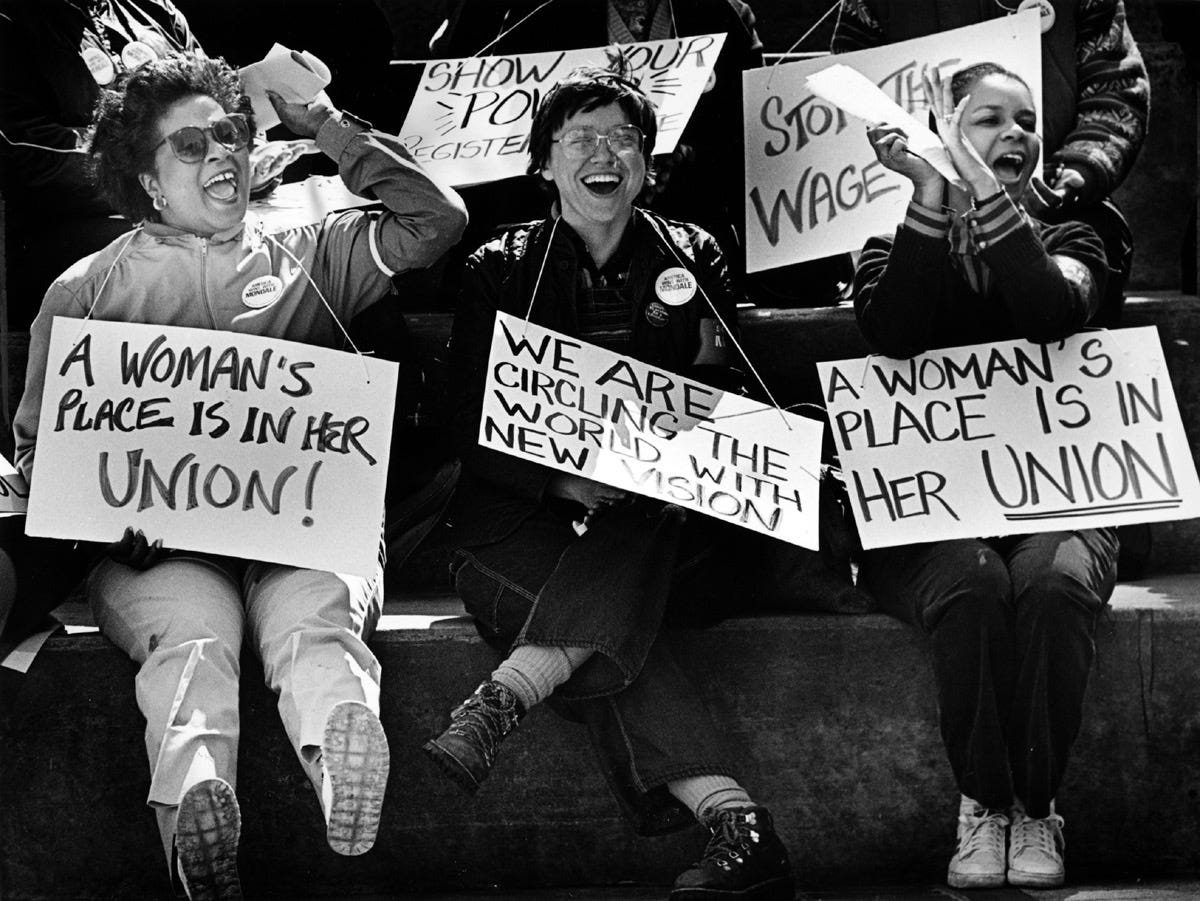

And there’s no better day to remember that than today, May 1st, International Workers' Day, born from the 19th-century struggle for the eight-hour workday and led by labour, socialist, and Marxist parties. In many countries, it was women textile workers who led the first strikes, demanding dignity, fair wages, and time to rest. Communist and socialist movements throughout Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe embraced May 1st as a global symbol of worker solidarity and revolutionary struggle.

This “holiday” is a reminder that every gain workers have made: an 8-hour workday, paid leave, safety laws, etc., was won through organized resistance, often led by the most exploited.

Class clarity builds solidarity, and solidarity makes action possible.

🗓️ Next issue: The Origins of Wealth

Fan the Flame 🔥

Real change doesn’t require doing everything. It requires doing something, consistently, consciously, and in community.

What You Can Do Now:

Ask your friends or coworkers how they define “middle class.” Then challenge that definition: is it based on income, ownership, or aspiration?

Think of three people in your life whose identities or jobs are different from yours. What material interests do you share? Rent protections? Public healthcare? Workers’ rights?

Look up the unions active in your city.

Revolutionary Spotlight:

A poor woman of Black and Indigenous heritage, Lucy Parsons became one of the most radical voices of the U.S. labour movement. A founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), she organized workers, led protests, and challenged the ruling class, earning her the label “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.” She shaped the origins of May Day and continues to influence worker resistance.

Revolution in Action

May 1, 1886 – The Haymarket Affair:

The origins of International Workers’ Day stem from the 1886 Chicago labour strike demanding the 8-hour workday. When police opened fire on protestors, workers rallied, and tensions escalated into what would become known as the Haymarket Affair. The state executed four labour organizers, anarchists and communists without a fair trial. But their sacrifice sparked a global tradition of working-class solidarity, now commemorated every May 1st, though interestingly and purposely, in the U.S., they celebrate Labour Day on a different day.

Further Reading

Race for Profit – Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Women, Race & Class – Angela Y. Davis

Class Counts – Erik Olin Wright

Social Class in the 21st Century – Mike Savage

It's impressive how this piece is able to reframe this topic and help people understand it. I've talked to Gabriela many times about this and similar topics, and even I'm reading this week's article, going 'hm, I haven't thought of it that way.'

This week, it was the section about identifying as middle class, and I've never thought twice about it. But what does it mean, and whose interests are aligned whenever we think or self-select identifications in certain ways? It's all very interesting.

Also really appreciate the links for the extra reading!